—Charles Dickens, Bleak House

It was hard to know what to do or what not to do, but in order to survive Strike went by three unbreakable rules: trust no one, don't get greedy, and never do product. Most people who lasted out here lived by the same rules Strike did, plus rule number four, which was kind of a balancing act with rule number one: you got to have someone watch your back. You got to have a main somebody to cover your ass. You didn't have to trust him completely, but alone is tough. There's always something you'll need help with. Bail, jail, collections, muscle, the impossibility of being in two places at one time. That's why Rodney had Erroll.

...

The Virus wasn't a disease; it was a personal message from God or the Devil, and in Strike's imagination the messenger would look something like Erroll Barnes. Erroll having the Virus was like death squared.

"Yeah, ol' Erroll..." Rodney sat down again. "The nigger mostly smoke and bluff now, you know, but everybody so scared a him on legend alone, man, that people are going to be walking tippy-toe two years after he's dead.

—Richard Price, Clockers

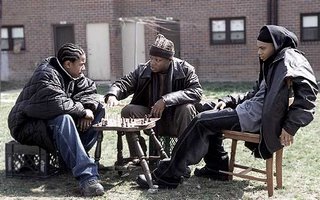

One upon a time, in a fictional city called Baltimore in a fictional state called Maryland in a fictional country called United States, there lived four young men who sold drugs retail at the Pit, a grassy area in the midst of low-rise housing projects. They were called Dee, Bodie, Poot and Wallace when they called one another by name. Bodie will die on Sunday night as the fiftieth episode and the fourth season of The Wire, an HBO original series, comes to a close. Wallace died in episode twelve. Dee died in what is in my view the single best episode, number nineteen. "All Prologue" is its title.

One upon a time, in a fictional city called Baltimore in a fictional state called Maryland in a fictional country called United States, there lived four young men who sold drugs retail at the Pit, a grassy area in the midst of low-rise housing projects. They were called Dee, Bodie, Poot and Wallace when they called one another by name. Bodie will die on Sunday night as the fiftieth episode and the fourth season of The Wire, an HBO original series, comes to a close. Wallace died in episode twelve. Dee died in what is in my view the single best episode, number nineteen. "All Prologue" is its title.The four young men we were introduced to in season one were already, as is Strike when we're introduced to him at the beginning of the Price novel, "out here." Price, even before the second excerpt above, provides Strike's history. That is the way of novels. The moving picture mediums are, by necessity, different. The characters are not played by words which evoke mental images. They're played by actors and actors age, eventually, like everyone else. By the end of season two it was fairly easy to compare the contemporary Baltimore created by David Simon (a reporter) and Ed Burns (a homicide detective and teacher) with the Victorian London created by Charles Dickens, but it is with season four that the depth that the printed page can provide is achieved on video.

This season followed four boys into the places where they sleep, the places where they learn, and the places where they hangout. Would any or all of the four be another Dee or another Bodie or another Poot or another Wallace? While answering that question it also followed the fortunes of a white City Councilman as he sought to become the first white Mayor in a generation [the real deal in this regard got himself elected Governor a month back], an addict-informant-entrepreneur in need of companionship and protection, a task force in need of new direction after bringing to justice the target for whom they were first brought together, a legendary gay stickup man with a code put in jeopardy because he makes use of a tip on a high-stakes poker game, a police turned middle-school math teacher, a police commander turned researcher and, among many others still, the enforcers for the new top drug dealer in the areas of west Baltimore where we watched Dee, Bodie, Poot and Wallace—nothing interesting about thee—try to last.

The season began with a woman buying a nail gun in a suburban hardware store. Once the transaction was complete she got in on the passenger side of a van. The driver is a guy named Chris and with Chris the Erroll Barnes of Clockers finally became a reality of sorts. Barnes was in a way known to me before I read Clockers [someone of the type took notice of me for a split second a very long time ago] and was easily, for me, the most memorable character of that novel. The new top drug dealer isn't leaving any bodies. Homicide, therefore, isn't getting any crimes to investigate on his account and that nail gun, bought by his enforcers Snoop and Chris, is part of the reason why. We know where the bodies are early. The four boys we're following will encounter and discuss Chris more often than they'd like and will know where they are a little later and, late in the day, the police, and one in particular, because of one of the boys, will have enough clues to know where, too...and then a body will be recovered and Bodie (...and then I'm standing here like a asshole holding his Charles Dickens 'cause I ain't got no muscle, no backup) will die alone as a sorrowful Poot withdraws.

The season began with a woman buying a nail gun in a suburban hardware store. Once the transaction was complete she got in on the passenger side of a van. The driver is a guy named Chris and with Chris the Erroll Barnes of Clockers finally became a reality of sorts. Barnes was in a way known to me before I read Clockers [someone of the type took notice of me for a split second a very long time ago] and was easily, for me, the most memorable character of that novel. The new top drug dealer isn't leaving any bodies. Homicide, therefore, isn't getting any crimes to investigate on his account and that nail gun, bought by his enforcers Snoop and Chris, is part of the reason why. We know where the bodies are early. The four boys we're following will encounter and discuss Chris more often than they'd like and will know where they are a little later and, late in the day, the police, and one in particular, because of one of the boys, will have enough clues to know where, too...and then a body will be recovered and Bodie (...and then I'm standing here like a asshole holding his Charles Dickens 'cause I ain't got no muscle, no backup) will die alone as a sorrowful Poot withdraws.The Wire is, as its advertising claims, a masterpiece and a masterpiece to be compared favorably to a Bleak House. As the fourth season ends we'll have seen the last of Bodie and quite possibly the last of that legendary gay stickup man with a code (looks like he's leaving town) who is to-date, as far as I'm concerned, The Wire's most memorable character. They should create a series around him. Call it Omar Comin'.

Meanwhile, on HBO, it's on to Rome and Max Pirkis as Octavian and then James Gandolfini's final turn as Tony Soprano and then...

1 comment:

The output of HBO in the last few years seems to be infinitely superior to anything on the major networks.

Why is that?

Post a Comment