---------------------------------------------

That's strange. Ogin's always been known by her kimonos. And way off her turf.

I'm sure. She had a perm and stank of perfume.

A perm, Ogin? Times sure have changed.

On V-J day, August 15, 1945, the 35-year-old Japanese director Akira Kurosawa.... He's going to tell the story in a rather lengthy excerpt from his 1982 Something Like An Autobiography, but before he does I want to emphasize that this passage came as no surprise when I read it many years ago. Akira Kurosawa is, I believe, the greatest storyteller the movies have known and to the outcome of World War II a lot of that is owed.

...And now the opening paragraphs of the short chapter entitled "The Japanese":

After the war my work went smoothly again, but before I begin to write about that, I would like to look back once more at myself during the war. I offered no resistance to Japan's militarism. Unfortunately, I have to admit that I did not have the courage to resist in any positive way, and I only got by, ingratiating myself when necessary and otherwise evading censure. I am ashamed of this, but I must be honest about it.

Because of my own conduct, I can't very well put on self-righteous airs and criticize what happened during the war. The freedom and democracy of the post-war era were not things I had fought for and won; they were granted to me by powers beyond my own. As a result, I felt it was all the more essential for me to approach them with an earnest and humble desire to learn, and to make them my own. But most Japanese in those post-war years simply swallowed the concepts of freedom and democracy whole, waving slogans around without really knowing what they meant.

On August 15, 1945, I was summoned to the studio along with everyone else to listen to the momentous proclamation on the radio: the Emperor himself was to speak over the air waves. I will never forget the scenes I saw as I walked the streets that day. On the way from Soshigaya to the studios in Kinuta the shopping street looked fully prepared for the Honorable Death of the Hundred Million. The atmosphere was tense, panicked. There were even shopowners who had taken their Japanese swords from their sheaths and sat staring at the bare blades.

However, when I walked the same route back to my home after listening to the imperial proclamation, the scene was entirely different. The people on the street were bustling about with cheerful faces as if preparing for a festival the next day. I don't know if this represents Japanese adaptability or Japanese imbecility. In either case, I have to recognize that both these facets exist in the Japanese personality. Both facets exist within my own personality as well.

If the Emperor had not delivered his address urging the Japanese people to lay down their swords—if that speech had been a call instead for the Honorable Death of the Hundred Million—those people on that street in Soshigaya probably would have done as they were told and died. And probably I would have done likewise. The Japanese see self-assertion as immoral and self-sacrifice as the sensible course to take in life. We were accustomed to this teaching and had never thought to question it.

I felt that without the establishment of the self as a positive value there could be no freedom and no democracy. My first film in the post-war era, Waga seishun ni kuinashi (No Regrets for Our Youth), takes the problem of the self as its theme.

And so in 1946 there was Waga seishun ni kuinashi (No Regrets for Our Youth), most notable as the only Kurosawa movie centered on a woman. She is played by the actress who would shortly become the most important woman in Yasujiro Ozu's post-war movies and, other than his mother, his life, Setsuko Hara. In 1947 it was Subarashiki nichiyobi (One Wonderful Sunday), unseen here. In 1948, Kurosawa worked with the actor Toshiro Mifune for the first time. Yoidore tenshi (Drunken Angel) is most memorable for Mifune's performance as the consumptive gangster who is losing his place because the ex-boss is back from prison. Then Kurosawa became something of an independent and for-hire director when he left his studio, Toho, after three ugly strikes. In March of 1949, Shizukanaru ketto (The Quiet Duel), also unseen, was released and the stage was set.

It was an unbearably hot day.

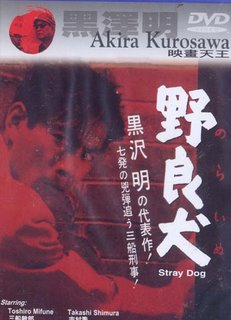

Kurosawa writes that most of those who saw Shizukanaru ketto (The Quiet Duel) did not get his main point (never disclosed) and so he decided to try again with Nora inu (Stray Dog). He wrote a novel in the style of Georges Simenon's social crime novels and then survived what he found to be the difficult process of transforming it into a screenplay. After the titles over a panting dog, a voice-over says "It was an unbearably hot day" and we come in on a police detective, Toshiro Mifune as Det. Murakami, telling his Lieutenant that he has lost his gun. What follows is a flashback in which his pocket is picked on a train as he's returning from target practice. There are numerous types of shots and lenses on display. The action isn't particularly well choreographed or photographed as he chases the man he thinks has his gun, but, given that failing to catch him is necessary to the plot we take a wait and see attitude. Det. Murakami goes to look at mug shots and finds the picture, rather too quickly, of a woman in a kimono who now wears a dress, sports a perm, stinks of perfume and actually picked his pocket. The pickpocket expert knows her and where to find her. There is an amazing shot in which camera and actress move at diagonals to one another as they talk to her. She complains at one point that her civil rights are being violated. When she leaves he follows her through the streets and everything begins to work. Finally, he breaks her down and she brings him food and drink and a suggestion as to where to go to look for his gun. He takes her suggestion and for over eight minutes we're given a look at the black market in post-war Japan while he hopes to make contact with someone who rents out guns. In a ruin it finally happens, and in his desperation to get his gun back he makes a mistake that will have terrible consequences and will bring him a mentor, Takashi Shimura as Det. Sato. And all the while the action is filmed in unconventional and varied ways and we become more and more caught up in his stubborn quest as everyone sweats and fans themselves.

Many events and shots later things build to a stunning climax in which Mifune finally confronts another of the Seven Samurai (in addition to Mifune and Shimura two of the other five debut for Kurosawa in this movie) and then has one final brief encounter with Shimura before the movie ends. Shubun (Scandal) and then Rashomon were released in 1950 and a year later on the Tenth of September in One Thousand, Nine Hundred, Fifty-One Rashomon won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and the title and the director's name began to be seen and heard all over the planet. A year later there was Ikiru and two years after that there was Shichinin no samurai (Seven Samurai).

The movies whose impact upon me I imagine most readily compare to that of Nora inu (Stray Dog), released in October 1949, had I seen it before Kurosawa's later movies, are Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets (1973) and Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs (1992). Nothing prior suggested that what I was about to see would be anything special. Ever afterwards I knew the director's name.

Look, how pretty that is. In the last twenty years, I've completely forgotten how wonderful the stars are.

In many ways, what Nora inu (Stray Dog) is about is recovering a sense of self, whatever the cost. After Ogin, the pickpocket, gives Det. Murakami the food, drink and suggestion she lays back, sees the sky, and comments on how pretty it is and how wonderful the stars are. When Takashi Shimura as Mr. Watanabe "wakes up" in one of the masterpieces, Ikiru, he notices a sunset for the first time in years.

In the end, Kurosawa concluded with a movie that reminds me of the other master, Yasujiro Ozu, and particularly Sanma No Aji (An Autumn Afternoon), right up to its final scene. Madadayo is about a professor who retires before World War II and is then looked after by a group of devoted former students during the next twenty or so years. Every year they get together to celebrate his birthday and as one of the rituals the professor drinks a large glass of beer and the students serenade him with Mahda-kai? (Are you ready?) to which he replies Madadayo! (Not yet!). Over time Japan loses a war and rebuilds and becomes Westernized. At the later party the students are joined by their wives and children. The movie was released in Japan in 1993, but only got a release in the United States in 1998, the year Kurosawa died. Roger Ebert concluded his 3/28/98 Chicago Sun-Times review:

The movie is as much about the students as the professor; as much about gratitude and love as about aging. In an interview at the time of the film's release, Kurosawa said his movie is about "something very precious, which has been all but forgotten: The enviable world of warm hearts." He added, "I hope that all the people who have seen this picture will leave the theater feeling refreshed, with broad smiles on their faces."

Well, I left with a broad smile on my face, but not because I'm a sucker for the world of warm hearts. No, it is that final, incredible scene. We're in Ozu's Japan until the final scene. The professor is 77 or so and ill and the students look down upon his sleeping form and wonder what he is dreaming about. And then we see what he is dreaming about. A young boy is looking for a place to hide among haystacks. Others are calling out Mahda-kai? (Are you ready?) and he is calling back Madadayo! (Not yet!). And then he finds a place and as he is lying down he notices the sky and he's transfixed. The camera follows his line of sight into the yellows and pinks. Pure, glorious, Kurosawa to close.

Ikiru means "To Live" and in post-war Japan no two men lived better or more productively than Yasujiro Ozu and Akira Kurosawa. The humanity and the sense of wonder that they brought to the movies they directed are a tribute to all that is best in the art form and my gratitude for all the wonderful hours in the dark that they've afforded me is very great indeed.

Arigatou gozaimashita.

4 comments:

Wow. Loner, what a review! You may've achieved literature here. It even builds a cinematic climax; the dying old man dreaming of his youth, of seeking a place to be, while those who love him watch in respect and wonder, brought a lump to my throat. Thanks for the good work.

I'll second that. I was arrested at the beginning by Kurosawa's recounting of August 15, 1945.

PS - For those interested in reading all Loner reviews - just type Loner in the search engine at the top of the page, this is the eighth and they are all well worth reading.

That is a very powerful passage--that a hundred million were thinking of suicide, and that a mere word from one man released them in a matter of minutes back into the world of the living. The event is close to us in time and proximity, but from an entirely different world. Can't help but wonder about the warrior-mystic MacArthur and his like-hearted peer, Patton. Both remorseless in war yet keenly respectful of social (not political!) culture of the vanquished enemy, both ultimately brought low by the new post-war world, the new world here and now and changing before our very eyes into something--now as then--yet unknown.

My thanks, Buddy, Rick, David and Skook. My editor, MHA, will confirm, I think, that all I notice are the missing commas.

Regarding Patton and MacArthur, Buddy, I couldn't agree more, and I'd also like to note that Secretary of War Stimson insisted that Kyoto, at the top of the atomic bomb target list, be removed and fought, successfully, every attempt to put it back on. He'd been there. He knew.

Best.

Post a Comment